Chapter 4: East

Dairy products are a staple food for many Canadians. From cream in our coffee, to the cheese and butter in a sandwich, to the yogurt and ice cream we eat by the spoonful, milk-based foods are consumed from morning to night. Dairy farming is also one of the country’s oldest industries. There are dairy farms in every province, but most are based in Quebec and Ontario.

- 3,613 farms

- 309,300 cows

- 163,100 heifers

Ontario

- 5,368 farms

- 346,600 cows

- 154,300 heifers

Quebec

Quebec alone has nearly half of Canada’s dairy farms. The province earns almost 40% of the country’s dairy revenues.

Dairy history

Dairy farming (also called dairying) is one of Canada’s oldest industries. French explorer Samuel de Champlain brought two cows to his colony and created a dairy farm in 1626 at St. Joachim, Cap Tourmente. By 1671, there were 866 cattle on Acadian farms.

Dairy farming began to gain popularity in Quebec during the 19th century, when many farms shifted from wheat production to dairying. The government sent agents to educate farmers about the commercial opportunities of dairy, and new producers emerged around the towns and railways. By 1900, dairy was the biggest agricultural product in Quebec.

Factory cheese making was introduced to Ontario in 1864. The province has always had a diverse agricultural sector, including dairy farming, which grew steadily into the 20th century. By 1900, cheddar cheese from Ontario was sold to 60% of the country’s English-speaking market.

The Dairy Farmers of Canada (DFC) organization was created in 1934 to represent the interests of Canadian dairy farmers and the industry at large.

About dairy products

What’s in milk?

Milk fat + protein-rich solids + water

New technology makes it easier to separate milk into its component parts. Manufacturers strain off the water to create protein concentrates, which are easier and cheaper to ship than raw milk. These protein substances also make cheese production more efficient.

Dairy cattle are raised for their ability to produce large quantities of milk with high butterfat, protein, calcium, casein and sugar content.

The Canadian dairy industry uses 7 breeds of cattle. These breeds are taller, and have more triangular, elongated bodies than beef cattle.

-

HolsteinThe most common and

HolsteinThe most common and

highest producing

dairy cow. -

AyrshireKnown for their hardiness

AyrshireKnown for their hardiness

and their ability to convert

grass into milk efficiently. -

JerseyLow body weight and

JerseyLow body weight and

genial disposition makes

them easy to maintain. -

GuernseyIts milk has a golden

GuernseyIts milk has a golden

tinge due to high levels

of B-carotene. -

CanadienneThe only breed of dairy

CanadienneThe only breed of dairy

cattle developed in Canada. -

ShorthornKnown for their durability,

ShorthornKnown for their durability,

longevity, and ease of calving. -

Brown SwissIts milk contains 4%

Brown SwissIts milk contains 4%

butterfat making it excellent

for cheese production.

How does milk become cheese?

How much dairy do

Canadians eat?

Per capita consumption of dairy products in Canada, 2016

Changing dairy

preferences

Milk

- Sales of fluid milk dropped 1% between 2015 and 2016.

- 2% milk is the most popular drinking milk in Canada, representing almost 50% of fluid milk sales

- Chocolate milk sales grew by 19 million litres between 2012 and 2016

- Sales of 2% and 3.25% milk are rising, while sales of 1% and skim have dropped slightly

Cheese

- Average cheese consumption per person grew by almost a kilogram between 2007 and 2016

- Cheddar and fine cheese saw the highest growth

- Cottage and processed cheese sales declined

Butter

- Butter consumption per person grew by nearly half a kilogram from 2007 to 2016

Yogurt

- Yogurt sales have been steadily increasing over 10 years

- From 2007-2016, average yogurt consumption grew by 43.7%

- The average Canadian now eats over 11 litres of yogurt each year

Ice Cream

- Ice cream consumption dropped between 2007 and 2016

- The average Canadian now eats 4.28 litres of ice cream per year, vs. 8.04 litres in 2007

Dan Hayes sets out to explore the issues facing dairy production in Canada, beginning his journey with a look at animal welfare on a typical dairy farm.

Why is dairy

important?

Canadians eat a lot of dairy products. From coast to coast, the average person consumes many litres and kilograms worth of cheese, milk, yogurt, butter and other dairy-based foods every year.

Dairy production also supports the Canadian economy. Dairy farms provide nearly 19,000 jobs, while dairy manufacturing employs nearly 23,000 people. Add up $17.7 billion in annual dairy shipments and $235.3 million in dairy exports, and it’s easy to see why dairy production matters to so many Canadians.

Global dairy consumption per capita in 2015

Economic impact

In 2015, Canada’s 12,000 dairy farms reported net receipts of about $6 billion. Thanks to the work of 950,000 cows, our country exported $112.6 million in dairy products to the United States alone in 2016.

How Canada manages dairy supply and demand

Ensuring the health of

land, people & animals

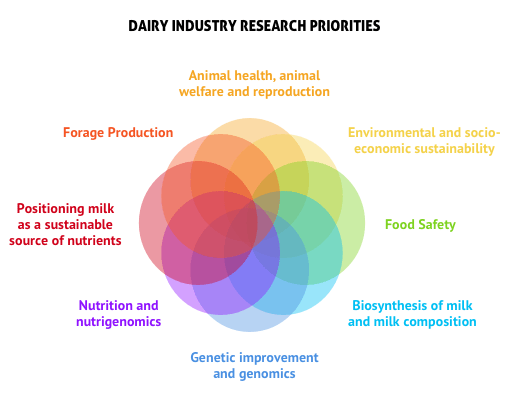

Today’s dairy farms face a number of challenges.

They also have many environmental and ethical issues to manage as they weigh the benefits of increased production against concerns for people, animals and the environment.

1. Environmental damage

Dairy farming uses important natural resources and produces greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change.

Where do the greenhouse gasses (GHGs) come from?

Major GHGs released from dairy farms include methane, nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide. Most of these GHGs come from three sources:

The methane gas that cows release are called enteric emissions. It might sound funny, but these emissions are a significant problem. According to a 2015 report, 27% of Canada’s methane emissions come from agriculture, and livestock emissions represent the majority of these farm-based methane emissions.

2. Large-scale industrial production

Canada’s supply management practices have set the stage for several changes in the dairy industry.

Farms are disappearing, but the remaining ones are getting bigger.

In 1976, Canada had almost 97,000 active dairy farmers with 1.99 million cows. That’s about 21 cows per farm. In 2011, there were just 14,883 dairy farms with 961,726 cows, or 65 cows per farm.

At the same time, dairy farms are producing more milk. In Ontario, the average milk output per cow doubled between 1976 and 2012. The small-scale family farm with small or modest milk production is giving way to large-scale industrial farms.

When dairy farms get bigger and more mechanized, the potential for environmental contamination and animal welfare issues increases. Issues of fairness arise, too. Should an increasingly smaller number of farms and dairy producers receive the benefits of Canada’s price protection strategy? Should we pay more at the grocery store to prevent other countries from importing their dairy products?

It’s a complicated issue. According to the Dairy Farmers of Ontario (DFO), farmers are passing on their productivity gains (the ability to produce and ship more milk from fewer cows) to consumers, so their own prices have increased at a lower rate than other foods and agricultural commodities.

3. Urban-rural border issues

In the past several decades, some municipal areas have passed land use laws designed to protect farmland from urban sprawl. For example, Ontario’s provincial government created a 1.8-million-acre greenbelt in 2005. It runs north of Toronto, Hamilton and the suburbs of these cities. The greenbelt land must be used for agriculture – but it also brings farms into close contact with houses and suburbs.

Many people like the idea, but not always the daily reality of living near farms. That’s why saving the land from development doesn’t always save the actual farms. Running a farm near a city can be challenging. There’s more traffic, less agricultural infrastructure and land prices are higher, which can drive many farmers to hang up their milking buckets.

Photo credit: Ian Willms

4. Animal welfare concerns

Dairy organizations say they are committed to providing top-notch animal support, including nutritious food, healthy living conditions and regular veterinary care. At the same time, large-scale dairy farming can involve practices that raise questions about animal welfare.

Dairy cows in industrialized farms (where machines often perform the milking) can also get a painful condition called mastitis, which creates infection and inflammation in the mammary glands.

Cows don’t produce milk unless they are birthing calves. Dan explores how calves are dealt with and the hard decisions that have to be made with male calves that will never produce milk.

What is being done to

help?

The Dairy Farmers of Canada proAction Initiative

Introduced by Dairy Farmers of Canada in 2012, this customer assurance program is designed to increase dairy industry transparency. Farmers offer proof of their milk quality and safety standards. They also pledge to continually improve animal health and welfare and environmental stewardship.

Saputo Dairy Care Program

At the University of Guelph’s Campbell Centre for the Study of Animal Welfare, a $50,000 gift from Saputo Inc. created this dairy welfare education program for practicing dairy veterinarians and dairy producers. It also includes a dairy welfare rotation for Doctor of Veterinary Medicine students.

Climate impact

mitigation

Consumer awareness

As more Canadians understand the potential benefits and drawbacks of family farms, versus large-scale industrial farms, they can make informed choices about the dairy products they buy and consume.

Organic dairy products are typically safer and more sustainably produced, with a greater focus on animal (and human) welfare. Like all organic food, they are also produced without:

- Synthetic pesticides, herbicides, fungicides, fertilizers

- Synthetic growth hormones or antibiotics

- Fossil fuel fertilizers or sewage sludge

- GMOs

Economics

Supply Management

Canada’s supply management system for dairy is often in the news. It is designed to balance milk product supply with Canadians’ dairy product consumption. While it has flaws and critics, the Canadian Dairy Commission says that it works to create a stable dairy industry. It protects Canadian dairy farms from changing national and international markets, and changing trade rules in an increasingly globalized market.

The Ingredient Strategy

In 2016, Ontario reduced the price of milk used primarily to make dairy ingredients, such as protein powder for smoothies. Excess quantities of these non-fat solids were being used for low-grade animal feed, yet inexpensive milk protein isolates were being imported. Several Canadian processors have now invested in new facilities to process the lower-class milk and create more dairy ingredients for sale.

Alternative sales models

In addition to government and industry management, many dairy farmers are taking matters into their own hands. They’re creating new ways to reach local customers, including:

Environmental

responsibility

Dairy industry initiatives

Dairy Farmers of Canada and other mainstream industry stakeholders are leading a variety of sustainability projects, new initiatives and farming techniques. These include:

- Research projects focused on reducing greenhouse gas emissions

- Life cycle assessments, which examine the environmental and social impacts of specific dairy products throughout their full life cycles

- Sustainable natural resource managment – caring for animals and effectively managing soil, air and water quality

Organic dairy in Canada

The principles of organic farming (no antibiotics, hormones, GMObased feed, GM animals, humane animal treatment, energy balance) promote sustainability and environmental responsibility.

Dan Hayes explores the practices employed by organic dairy farmers to discover the benefit to the consumer and the animal’s welfare.

Innovative tools &

techniques

Nutrient management

The Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs has a nutrient management assessment tool called NMAN. This tool helps farmers to determine the best ways to store, treat and apply materials like manure. Reducing chemical fertilizer applications can also help farmers save money and increase profits, while better protecting the environment.

Dairy Production Sustainability Assessment Tool

Dairy Farmers of Canada has an interactive, online tool designed to help farmers meet their sustainability goals. First they learn and assess, then measure and benchmark, and then take action. The tool covers field operations, on-farm activities, farm management, economic performance, community relations, workers’ well-being, and cattle management.

How one cow contributes to a sustainable food system

Livestock Water Recycling

This private company provides manure treatment technology, helping farms to reduce GHGs, concentrate and segregate nutrients for strategic fertilizer application, and recycle clean, reusable water.

Diagram of the LWR system

Guernsey cows

Eby Manor Farm in Waterloo, Ontario has 60 milking Guernsey cows. These cows receive GMO-free feed and produce milk that contains A2 casein protein, which some nutritionists believe is better tolerated by people who have allergies, lactose intolerance and other health concerns. Guernsey milk is also high in beta-carotene and calcium.

Sustainable

perspective

Dairy farming in Canada has a rich and productive history. It creates jobs, and generates income for farmers, producers and retailers. Many Canadians also love

to eat dairy products.

As farms focus on sustainability, they are exploring technologies like biogas and recycled bedding. They are also returning to their roots. Many organic and conventional farmers alike are seeing how the dairy farm, like other farms across our country, can be an integrated system – a healthy cycle of nutrients, cows, dairy products and ecosystems that work in harmony together.

How to support

sustainable dairy

Get to know your farmers. Whenever possible, choose dairy products that are sourced from farms working on sustainability – from reducing their carbon footprint to helping cows live healthy, happy lives.

I think organic means different things to different people. For me, it’s about the welfare of the cow. It’s about being careful and considering the environment when you’re farming. It’s about making a more nutritious product, in addition to the fact that there are no pesticides or artificial fertilizers or hormones in your products.Marshall King, Ontario Organic Farmer’s Cooperative